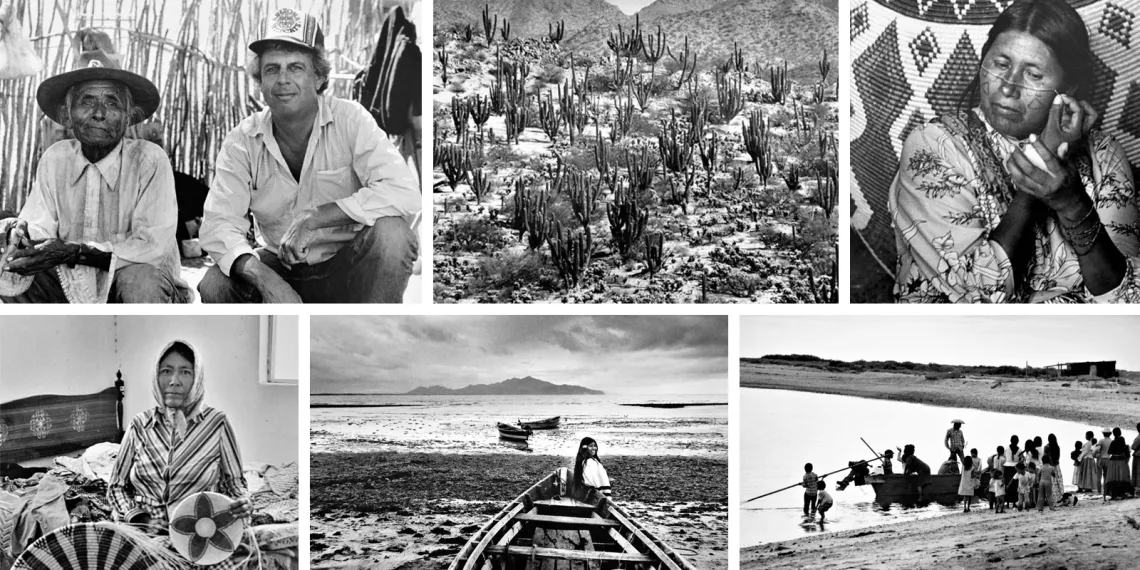

We sat down with photographer and research associate in the Southwest Center, David Burckhalter to discuss his long-range documentary study of Seri Indians.

In 1970, David Burckhalter was just starting to tinker with photography when he happened upon the nomadic Seri people, who live on Tiburón Island in the Gulf of California and the adjacent mainland in Sonora. This chance encounter began a 50-year relationship with the tribe, which numbers fewer than a thousand people. Today, Burckhalter’s work spans the globe, but he has returned once again to the Seris with a new book project.

Revista: How did you discover photography?

David Burckhalter: Everything in my life has seemed to be by chance, just by going out there and being open to what happens. I had a job in Hawaii; it was a bird project. I was in biology and entomology. One of the guys I worked with was buying a new camera and asked if I was interested in his old one. I had absolutely no idea what I was doing, but I was getting some good results. I decided to apply for grad school at the U of A. I was beginning street photography just around Tucson and realized I didn't know anything, but I was open to learning. I wasn't sure where it was going to take me, but I believed in myself and had confidence.

Revista: What first drew you to the Seris?

David Burckhalter: Because of the biology program I was in we started making field trips to Mexico. On one of those trips, I walked out of a restaurant after a shrimp dinner and a couple of beers and there were these Indian women in long dresses with their kids—they turned out to be Seris. What really attracted me were the faces; I couldn’t believe people looked like that. After I graduated, I said, I don't think I want to do [biology]. I had a master's degree and no job offers and only a couple hundred dollars in my pocket. I decided to go down to see the Seris; they were just starting to do these iron wood carvings and the women made beautiful baskets. So, at first, my entry into the villages was as a buyer of arts and crafts. I had an importing business. I still do that on a small scale. That started a long relationship that has gone on for 50 years.

Revista: What has changed in their community over the years?

David Burckhalter: When I landed there in 1970, their houses were ocotillo cactus-framed shelters and tarpaper shacks, and now they have permanent housing. They have a mold structure that they put up and a few concrete block shelters. They have access to cars and transportation—they used to be walking people—and the dress and appearance is totally different. All the men had long hair but now only women have long hair. The women used to face paint every day. And the men used to all wear cowboy hats but now they like baseball caps.

Revista: What is your current project with the Southwest Center?

David Burckhalter: I’m working on a book and it’s a magnum opus, you might say, about the Seris’ geography. I’ve been going out with a guide just to walk that land and focus on how their ancestors lived as nomadic people, living off the land and the sea. It’s been boots on the ground … for years I was just taking the same trip, but I realized that I really didn't know the land. I was just driving through it on the same roads every year. And so my project became that I want to explore the land to see what's out there, especially with the women, to find out where they go and how they do the harvest.

Revista: You’ve produced a lot of travel photography throughout the world. What has been the common thread throughout your work?

David Burckhalter: The attitude of respect that what you're doing is positive and you’re going to help transfer that—those cultural things that are being observed and recorded and documented—as a positive. It’s a hard decision to make because you realize that you're being intrusive, but on the other hand, there's this incredible image.

Revista: What’s been the most memorable or strikes you as your most important work?

David Burckhalter: I have an archive of 50 years of photographs of the Seris and I don't think anybody has anything close to that. … I've had a few people ask me what are your favorite photographs? The ones for me are the ones that are still in my head that I just didn't get. Or they were the ones that I was either too timid or I don't know why I didn’t take.

Revista: Are there any particular people or places you’d like to document but haven’t yet?

David Burckhalter: The Mayan Ruins. I've been to some but there's a bunch I would just love to see and then just go down there and walk around and eat great Mexican food. But right now, my whole focus is writing. What I'm trying to do is take people with me; the book I’m writing is like a personal geography. A personal journey. And I want the reader to feel like they're going with me and I'm showing them what's out there and in a creative, interesting way.

This interview has been condensed and edited.