Set in Mexico City, Alfonso Cuarón's Roma raises important questions about class, race and the aspirations of a developing nation. Discover a catalogue of other films that have showcased life in the capital.

In his 2018 Oscar-winning film Roma, Alfonso Cuarón delivers a portrait of a Mexico City in flux, exploring issues of race, class and ambition in an era marked by unease and unrest. The film also operates as a sort of paean to the neighborhood in which the writer-director spent his childhood; Cuarón painstakingly re-created the Tepeji Street home he grew up in and blocks in the surrounding neighborhood of Roma, which had been developed in the early 20th century with Art Nouveau mansions to house Mexico City’s elite, but by the film’s setting of the 1970s had waned in popularity.

Some of the best movies set in Mexico City similarly examine tensions between what the city was and what it is, says Carlos A. Gutiérrez, founder of Cinema Tropical, a Latin American film programming, publicity and distribution organization based in New York City, and the co-director of Tucson Cine Mexico, the longest-running festival of contemporary Mexican cinema in the United States.

“Mexico City is not as visually iconic as New York,” Gutiérrez explains. His selection of films that best encapsulate and illustrate life in Mexico City creates not a picturesque travelogue but a broad-spectrum glimpse of the disparate social classes who call the D.F., or Distrito Federal, home. The following iconic films portray Mexico City through the years and myriad social and political changes.

Los Olvidados (1950), Luis Buñuel

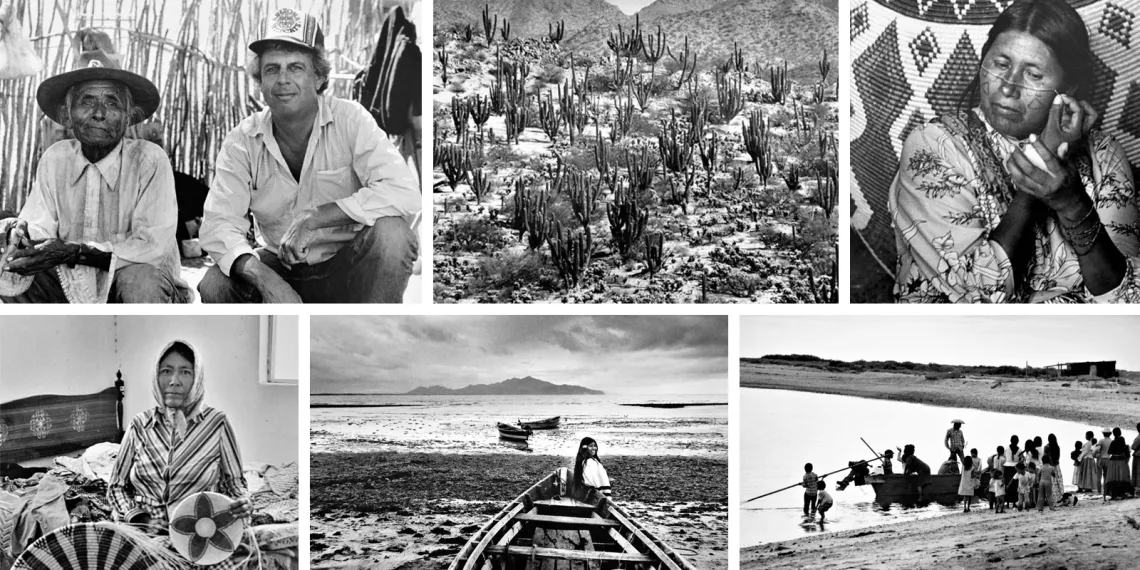

By the 1940s, Mexican cinema had become well known for its overly exoticized, mystical representations of the country’s indigenous population. Directors such as Emilio Fernandez, whose Xochimilco (Maria Candelaria) won the Grand Prix at Cannes in 1946, had created and popularized a Mexican iconography with stylized landscapes and depictions of indigenous people designed to enchant and amaze, instead of merely illustrate.

Buñuel’s Los Olvidados, a relentlessly grim portrayal of a group of poverty-stricken juvenile delinquents in Mexico City’s Nonoalco neighborhood eviscerated such overly romantic window-dressing and replaced it with visceral realism. Instead of morality and psychology, the film confronts existential issues about life and love; poverty is presented not to elicit pity but to present a reality that contradicts what had been commonly represented in the film industry of the time.

“The film is iconic in its portrayal of marginalized people,” says Gutiérrez. “During the decades when the country’s economy was growing at a fast pace, here Buñuel follows a group of kids in the slums of Mexico City, revealing that Mexico was not all perfect.”

Although the film was pulled from theaters after only three days amid outraged protests, critics were still able to recognize its merits; when it was selected for the 1951 Cannes festival, poet Octavio Paz even distributed an essay praising Buñuel, who’d go on to win Best Director that year for Los Olvidados. In 2003, the film was inducted into UNESCO’s “Memory of the World” program, which preserves documentary heritage of world significance.

El Callejón de los Milagros (1995), Jorge Fons

The movie adaptation of the 1947 Naguib Mahfouz novel Midaq Alley shifts the locale from 1940s Cairo to a run-down neighborhood in present-day downtown Mexico City, “and it works perfectly,” Gutiérrez says. “It gives a perfect representation.”

As its title implies, much of the four-part film is set on a single street where the characters live, work and struggle: Three parallel segments about alley life overlap and repeat scenes from varying perspectives before the final chapter revisits the narratives to resolve the plot lines—a gruff tavern owner who embarks on an extramarital gay relationship, a headstrong young woman (played by Salma Hayek, in her second movie role) spiraling into a life of prostitution, and a spinster whose quest to find love appears to be doomed.

Heated tempers, frustrated desires and dashed hopes commingle with warmth and gutsy humor, which earned the film a cache of international film awards and honors: 11 Ariel Awards (Mexico’s Oscar), including best film, best direction and best actress for Margarita Sanz; audience choice awards at the Chicago International and Guadalajara film festivals; and a special nomination at the 45th annual Berlin Film Festival for exceptional narrative quality.

Sexo, Pudor y Lágrimas (1999), Antonio Serrano

Serrano’s adaptation of his own long-running theatrical production set box office records in Mexico, grossing the equivalent of $12.4 million USD when it was first released. The battle-of-the-sexes comedy takes place amid the high-rise apartments and disenchanted yuppies of Polanco, one of Mexico City’s most posh neighborhoods.

“It’s a romantic comedy with a punch, focused on the ambitious Mexican middle and upper-middle class of the mid-1990s,” says Gutiérrez. As one of the first films in the wave of New Mexican Cinema, the movie not only spoke directly to the urban middle class but also served as a lifestyle fantasy for them, embedding philosophical musings on relationships inside an aspirational, glossy rom-com.

Sexo, Pudor … earned the audience award at the Guadalajara Film Festival, and won Ariel Awards for best original script, best actress, best original score, art direction and set design. A sequel is planned to begin production this year.

Amores Perros (2000), Alejandro G. Iñárritu

Iñárritu’s directorial debut is “a key film for Mexican cinema as it brings together the different classes and characters of Mexico City,” Gutiérrez says. Like Los Olvidados, the film interweaves three tales that intersect at a defining moment, but it takes viewers at a breakneck pace on a pulpy, feverish, side-streets tour through the lives of characters who inhabit markedly disparate social strata—wealthy models and magazine publishers on one end of the spectrum, dogfighting hoodlums and contract killers on the other. (The same structure and immersion in the criminal underbelly were used in Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction, with which Amores Perros has often been compared, although it’s been argued that the former is designed to glamorize the gangster component whereas the latter merely exposes them for what they are.)

Amores Perros won 15 Ariel Awards, was nominated for Best Foreign Film at the Academy Awards and earned several international awards. It launched the careers of actor Gael Garcia Bernal and Iñárritu, who won back-to-back Academy Awards for Best Director in 2014 and 2015 (for Birdman and The Revenant) and was president of the jury at the 2019 Cannes Film Festival.

Güeros (2014), Alonso Ruizpalacios

This portrait of aimless Mexican youth may feel leisurely paced, but it still manages to pay simultaneous homage to French New Wave cinema, the “road trip” film canon and the transference of cultural heritage among generations.

During the four main characters’ road trip through Mexico City—the film’s chapters are named after different areas in the city—they pass time in hospital rooms, cul-de-sac homes and intellectual parties, taking wrong turns in untouched-by-tourism neighborhoods on their search for a mythical elderly musician. On a meta level, they’re also searching for meaning and purpose for lives that have been disrupted and upended by the 1999 strikes and student protests at the National Autonomous University of Mexico.

“It’s a bit like the film Slacker, but highly stylized, and attempts to address social disparities,” Gutiérrez says. Güeros won five Ariel Awards, including Best Picture and Best Director, in 2015.